- Home

- Steve Vernon

The Lunenburg Werewolf Page 4

The Lunenburg Werewolf Read online

Page 4

Dermot counted pennies for paces as they hiked up the hill, hungry for a pirate’s buried treasure—which was why he tripped over his feet and fell face-first halfway up the hillside. He reached forward as he fell and inadvertently caught hold of Tommy’s left heel.

“He’s got me!” Tommy howled aloud, thinking he was being attacked by ghosts. “He’s got me by the heel!”

Before Dermot could say a word, Tommy up and ran, kicking off his boots and screaming out into the darkness, looking for all the world as if he were figuring on running barefoot back to the old country.

Dermot tried to call him back, but it was too late. He shook his head and grinned. “I hope he stops running before he hits the water,” he said to himself, shaking his head sadly. “And he took the map with him. Well this was a wasted night, for sure.”

The old mare blew her breath out through her lips as if she secretly agreed with Dermot.

“Come on then, horse,” Dermot said. “Let’s get ourselves home. Annie will be waiting to laugh at me in the morning.”

Dermot turned the horse around. He glanced up through the branches of the tree ahead and saw the full moon looking down at him—the full moon and something else a whole lot brighter. The sky was lit up as if the stars themselves had caught on fire.

Dermot knew what it was right off. “Annie,” he whispered.

Then he leaped up on the old mare’s back and kicked his heels hard.

A Legacy of Ashes

The old mare galloped a second time into the darkness. The light in the distance tore up at the sky. Dermot leaned in and urged a little more speed from the old nag. At this rate, if the mare threw him, he would break his neck for certain. As it was, he might run the horse into a tree and break both their necks. He didn’t care. “Faster,” he whispered.

The old mare galloped like she had never galloped before.

But Dermot was too late.

When he got back to his home, it had burnt to the ground. The candle that Annie had left burning in the window had caught on the cotton curtains, and the fire had raced through the old cottage like a galloping stallion. There was nothing left but a legacy of cinder and ashes.

Dermot knelt in the ashes of his home. He wept a long time, until something caught his eye. He picked it up.

It was little Elias and Mara’s toy stick, somehow spared from the flames. Dermot squeezed the stick until white half-moons of frustrated tension shone on the backs of his fingernails.

Then he climbed grimly onto the back of his tired, piebald mare and brought the stick down hard and sharp against the old horse’s haunches. “Giddy up,” Dermot cried.

He rode down along the old Cliff Trail. He rode past the foolish buried treasure dreams of Strawberry Hill. He rode headlong down the length of Hangman’s Beach. He hit the pounding waves and kept on riding, straight into the deep black waters.

To this day people will talk about how you will see the flicker of a candle and a roaring flame in the heart of the dark McNabs Island wood. They will tell you that it is a ghostly memory of an orphanage that burned down a long time ago. They will tell you how there is a treasure buried on the island and no one has ever found it. They will tell you of how you will hear ghostly hoof beats galloping down the old Cliff Trail. They will tell you all of these tales as if they were three completely separate stories. Only a few know the truth behind the matter—that all of these tales are linked together like a single unyielding chain anchored in dreams, ambition, and a fool’s bitter regret.

If you travel just one hundred kilometres from Halifax, you will come to the town of Kentville. In the early nineteenth century, the town’s centralized location, on the hub of several roadways and coach routes and eventually a train line, made it a popular spot for wayfaring travellers. Kentville soon developed a reputation for rowdy drinking and horse racing, earning it the nickname “the Devil’s half acre.” The locals can tell you many intriguing tales of depravity and debauchery that took place in this era, but the most curious of them all is the story of a young painter’s brush with fate.

A Shortage of Rooms

The leaves were falling, one by one, like tattered scraps of some unfinished painting. It was autumn in Kentville. A travelling art supply salesman by the name of Walter Irving arrived in town on the train, encumbered with an overstuffed suitcase and three bulging sample trunks. He had come from Halifax, where he had been visiting his poor mad sister in the mental asylum. The girl had been committed the previous summer. Her senses had left her one night while she was sleeping. They found her in the morning giggling ceaselessly.

“I saw a ghost,” she’d sworn. “A painted ghost.”

Walter shook his head at the thought of it.

He was tired and hungry and ready for rest—only it seemed as if rest would be hard to come by.

“There’s an awfully big horse race going on in Kentville this weekend,” the conductor told him. “You’re going to have some trouble finding a place to stay.”

It turned out the conductor’s prediction was dead right.

“I’m afraid that I’ve only got one room left,” the hotel owner told Walter. “I’ve let it out to a friend of mine from Shelburne, but I am sure he wouldn’t mind sharing. How would that suit you?”

“That would suit me right down to my bones,” Walter answered.

“Have you had supper yet?” the owner asked him.

Walter sat down at a table with about forty men who were mostly interested in talking about the horse race. He finished his meal of stew and dumplings and chased it with a strong cigar and a pint or two of ale.

When Walter finished his dinner, he said his good nights and went directly to his room. He opened the door and was surprised to see a slender young man sitting upon the golden chaise lounge with a large leather portfolio balanced upon his lap. The youth was pale, inordinately so, and his skin seemed nearly transparent.

Of course, Walter thought to himself. This must be the guest from Shelburne that the owner spoke about.

“My name is Walter Irving,” Walter introduced himself, entering the room and bolting the door behind him. “I represent a firm that deals in art supplies.”

“A peddler, eh?” the young man replied with a charming wry grin as he open his portfolio. “And of art supplies? What a coincidence. I sketch a bit myself. My name is George Cushman.”

“An artist, are you?” Walter asked.

“Only an amateur,” George replied. “Would you like to see some samples of my latest work?”

Walter sat for over an hour, studying the young man’s artwork. The majority of the sketches were rough, yet they showed a deep and genuine talent. There was an authenticity to George’s pencil work, a certain quality that seemed to linger and haunt the salesman.

“Look as much as you like,” George said. “You may even keep them if you like. Where I am bound for, I will have no need of sketches. As for me, I believe it is finally time to seek my rest.” The young man stretched out upon the chaise lounge, closed his eyes, and fell into a sleep so deep that Walter could detect barely a trace of respiration.

Mesmerized, Walter continued to flip through the artwork. There were countless views of the Cornwallis River and the surrounding countryside—landscapes and portraits and roughed-out sketches. Walter was most struck by a portrait of a beautiful young woman with eyes that seemed to gleam like moonlit ice. She was smiling in such a way that seemed to promise laughter.

I’ve seen this face before, Walter thought.

He placed the portrait beside his luggage. In the morning he would ask the young man if he could keep it. After all, hadn’t George said that he could take whatever pieces interested him?

A Ghostly Visitation

Walter Irving blew out the flame of his bedside candle and lay there in the darkness. The bird’s-eye maple panelling seemed to stare at him

from the shadowed darkness, and from atop his luggage the face of the mysterious woman seemed to glisten and shine.

The next morning Walter woke up to find that young George had disappeared in the night. At first he was certain that the young man had robbed him, but when he checked, his belongings seemed intact. Even the portrait of the woman had not been touched.

Yet strangely, the door was still bolted from the inside.

Had George climbed out the window? Walter checked the window, but it was securely fastened.

Walter sat down upon his bed and puffed upon a morning cigar, trying to make some kind of sense out of the mystery. Then he rose and dressed and went downstairs to inquire as to the whereabouts of his roommate.

“Your friend from Shelburne seems to have vanished,” he told the hotel owner.

“In fact, he never arrived,” the owner replied. “His stage was delayed. I had told him to take the train, but he is stubborn like that. I found out so late in the evening that I did not think to trouble you and let you know, assuming you had already gone to sleep.”

“But what about the young artist who stayed with me?” Walter asked. “What about George Cushman?” He told the owner what had happened that night, then retrieved the portrait of the woman from his pocket as proof. When he showed the owner the portrait, the man turned ashen.

“I am afraid that you were sleeping next to a ghost last night,” the owner said. “The truth is, George Cushman hung himself in that very room.”

“Why didn’t you warn me?” Walter asked.

“I’m trying to run a hotel,” the owner explained. “If I were to warn every one of my customers about every bad doing that has gone on in these rooms, I might as well hang a ‘Hotel for Sale’ sign on the front door.”

The man did have a point.

“Why did he hang himself?” Walter finally asked.

“He couldn’t find a pistol, I expect.”

“You owe me a better answer than that.”

The owner nodded. “I guess I do,” he admitted. “Do you see that woman in the picture? She’s pretty enough, I suppose, but the sad truth is that she was the cause of it all.”

“Who was she?” Walter asked.

“Her name was Alice.”

“Is she still alive?”

“The last I heard she was living in an insane asylum up in Halifax. I hear she’s taken out a long-term lease.”

That’s when it hit him. Walter knew just where he had seen that woman before. In the cell beside his sister at the Halifax asylum.

“Incurable?” Walter asked.

“Irrevocable,” the owner replied.

“Tell me the story.”

“George Cushman was the son of a wealthy New York businessman,” the owner began. “He was an artist, by all accounts. That’s always a bad sign. A man gets to messing his mind up with imagination and such and there is no telling what end it will lead him to. He used to paddle a canoe up and down the Cornwallis River. I’d see him out there with an easel set up, painting his landscapes.”

The owner shook his head ruefully. “The darned fool should have known better. One day the canoe caught a snag and turned keel-over-kettle. It nearly drowned him. Alice pulled him out. She was the daughter of a fisherman, and Lord knew the trouble that she caught that day.”

“What happened?” Walter asked. “Did he fall in love?”

“He jumped in, was more like it. You know these artistic types. Intense is the word. He fell in love with Alice right then and there. He made his mind up that the two of them were going to live together happily ever after. He decided they would raise up a whole house-load of budding young art students. Too bad he didn’t think to let the girl in on his plans.”

The owner looked down at the painting. “He caught her at a garrison ball, dancing with a young officer. He quarrelled with her. He made such a scene that three of the troopers threw him out into the street. He came back to this hotel and he hid up in his room for three whole days. On the third day he hung himself. It was Alice who found him, the way I heard it. I guess she’d come to apologize for offending his brittle imagination.”

“It must have been bad for her,” Walter said.

“Bad?” the owner said. “It was outright ugly. She had no idea what was going on in his head. We found her sitting there in the scraps of his artwork, kneeling before his noosed-up corpse. Her hands were clasped white-knuckle tight and she was staring at the wall, not seeing a blessed thing. She hasn’t spoken a word since then, as far as I know. I expect she’s most likely sitting up there in her room in the asylum, still staring at the walls.”

Walter looked down at the portrait. The eyes seemed to follow him. “I think we ought to burn it,” he said.

So they laid a fire in the main fireplace and when the flames were crackling high enough Walter placed the portrait upon the fire. The flames licked and crackled upon the canvas. One would have thought that the oil-laden fabric would have easily kindled, but oddly, the painting proved resistant to fire. When the firewood died down into a bed of cinders and ash, the owner removed the cursed portrait.

“The flames haven’t touched it,” he said.

There was not even a trace of smoke damage.

“What will you do with the picture?” Walter asked.

“I will store it in the attic,” the owner replied. “She was a guest once, and I will make her welcome for as long as she needs to stay.”

And the painting is there still.

Deep in the heart of Cape Breton’s Richmond County, midway down Highway 4, lies the quiet little town of Grande Anse. Legend has it that if you travel along the Grandique Ferry Road approximately one kilometre from Grand Anse, you will come to a clearing. There, framed by a border of tall black spruce standing so stock still that they seem to be holding their needled breath and waiting for something to crawl out of that darkness, is what the local folk will fearfully tell you is the Black Ground.

The Black Ground is a sprawling field bisected by the nasty slashing scar of a long dirt road. There is a lake at one end of the field that some people believe to be bottomless. A series of wildfires have blazed through the field over the centuries and as a result the soil has blackened with ash. The blueberries and cranberries that grow in the field are known to be fat and juicy, but very few locals will dare to pick them.

Many believe that the Black Ground is haunted by a Bochdan—an ancient beast that came across the ocean from its Scottish homeland, stowed away on a ship of early settlers. A Bochdan is a kind of hobgoblin that feeds on fear and carrion. The Bochdan lives for mischief and mayhem of the darkest kind. It cloaks itself in shadow and favours sour ground. It hides in brooks and peers up at unwary wanderers just before reaching up suddenly and dragging them down to drown.

The older folk who live in the surrounding regions of the Black Ground swear they’ve seen inhuman figures dancing there in the darkness. They claim to have heard beastly sounds of baying out there beneath the moonlight, sounds that chilled their blood and caused their hearts to skip a beat or two.

They say that there was once a settlement on the Black Ground. People lived there and grew content in the belief that they could turn its cursed soil to good. But all that changed when two young Cape Breton boys witnessed a terrifying midnight parade.

Plans and Blueberries

One long, hot, and dusty August afternoon, Harold and Franklin Dunbar set out to pick blueberries on the Black Ground. But the blueberry picking soon gave way to a game of hide-and-seek, which just as naturally gave way to a sudden bout of tree-climbing, which of course led the boys to an hour-long ponder over the best location to build themselves a tree fort. Which was right about the time that darkness fell onto them like a great panther leaping down onto the back of an unwary traveller.

Out here on the Black Ground, the charred dirt seemed to gulp down

any trace of light. Even the moon and the stars seemed to blur and haze and shrink against the bleak black of that stretch of cursed Cape Breton wilderness.

“Can you see much?” Harold asked.

“Not much more than you can, I expect,” Franklin answered.

Which was right about the moment when something out there in the darkness screeched. It might have been a screech owl. It might have been a wild cat. It might even have been nothing but a long fir bough fiddling against a patch of tuneful tree bark. Or it might have been a ghost.

“We ought to light a fire,” Franklin said.

“Are you sure?” Harold asked. “The brush out here is awfully dry for lighting fires.”

Harold spoke the truth. It had been two weeks since the last rainstorm had soaked the surrounding woodland, and it was quite likely that a poorly laid camp blaze would risk a forest fire.

“I don’t care,” Franklin said. “I want a fire.”

“You’re scared, aren’t you?”

Which was right about when that whatever-it-was in the darkness screeched out a second time, even louder than the first.

Goosebumps waddled across a pair of scared young necks. Hair started to rise. Hearts beat at a double-gallop. And fear crept on in.

“Of course I’m not scared,” Franklin replied with a hastily swallowed gulp. “I am absolutely wet-my-pants-and-scream-like-a-little-girl terrified. ‘Scared’ just isn’t nearly a big enough word for the way that I feel right now.”

“It’s good to know I’m not the only one who is scream-like-a-little-girl terrified,” Harold replied as he scraped the fir needles away from a patch of dirt and started scooping out a firepit. “You get the wood and I’ll lay the fire.”

Franklin looked fearfully out into the darkness, waiting for one more screech. “How about you get the wood and I lay the fire?” he asked.

“I’ve got the matches,” Harold said. “So you need to go and get the wood.”

Flash Virus: Episode One

Flash Virus: Episode One Cat Tales Issue #3

Cat Tales Issue #3 Cat Tales Issue #1

Cat Tales Issue #1 A Fine Sacrifice

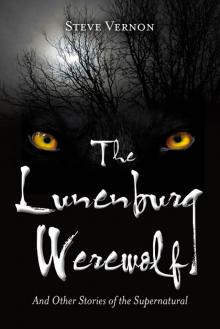

A Fine Sacrifice The Lunenburg Werewolf

The Lunenburg Werewolf October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1)

October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1) Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3)

Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3) Haunted Harbours

Haunted Harbours Wicked Woods

Wicked Woods Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2)

Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2) A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9)

A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9) Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7)

Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7) Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4)

Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4) Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out

Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Sinking Deeper

Sinking Deeper Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5)

Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5) Big Hairy Deal

Big Hairy Deal Maritime Murder

Maritime Murder Rueful Regret

Rueful Regret