- Home

- Steve Vernon

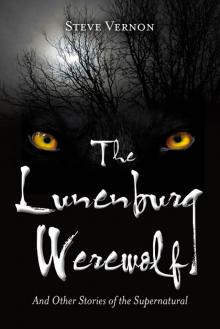

The Lunenburg Werewolf

The Lunenburg Werewolf Read online

And Other Stories of the Supernatural

Steve Vernon

Copyright © 2011, Steve Vernon

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3731 Mackintosh St, Halifax, NS B3K 5A5

(902) 455-4286 nimbus.ca

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Vernon, Steve

The Lunenburg werewolf : and other stories of the

supernatural / Steve Vernon.

ISBN 978-155109-886-9

1. Ghost stories, Canadian (English)—Nova Scotia.

2. Ghosts—Nova Scotia. 3. Folklore—Nova Scotia. 4. Haunted places—Nova Scotia. 5. Nova Scotia—History. I. Title.

BF1472.C3V474 2011 398.209716 C2011-903914-1

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia through the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage.

Acknowledgements

Introduction

The Lady in Blue (Peggy’s Cove)

Murder Island Massacre (Yarmouth)

Sunk by Witchcraft (Pictou)

The Phantom Ship of the Northumberland Strait (Pictou Island)

The Mare of McNabs Island (Halifax)

The Kentville Phantom Artist (Kentville)

Beast of the Black Ground (Grande Anse)

The Quit-Devil (Glace Bay)

The Mark of the Fish (Port Hood)

The Sight of the Stirring Curtains (Digby)

Aunt Minnie’s Black Cat (Cleveland)

The Haunting of Esther Cox (Amherst)

The Broken Heart (Lunenburg)

The Lunenburg Werewolf (Lunenburg)

The Capstick Bigfoot (Capstick)

The Ghosts of Oak Island (Oak Island)

The Fires of Caledonia Mills (Caledonia Mills)

The Tale of the Screeching Bridge (Parrsboro)

Three Selkies for Three Brothers (Cape Breton)

Ivy Clings to this Lodge (White Point)

Mrs. Murray’s Five Crying Babies (New Glasgow)

The Sad Story of the Stormy Petrel (Maitland)

Liam and the Lutin (Havre Boucher)

I’d like to thank Conrad Byers —storyteller, folklorist, and historian from Parrsboro, Nova Scotia—for his invaluable help with “The Tale of the Screeching Bridge.”

I’d also like to thank the folks at White Point Beach Resort for inviting me to tell some Halloween stories and for the help they gave me with Ivy’s story.

I’d like to thank the folks at Nimbus for the faith they continue to show in my work.

And lastly, as always, I’d like to thank my wife, Belinda, for putting up with me all these years. I could not believe in me if not for thee.

A story, at the heart of it, is an answer to a question.

One question I often hear as a storyteller is, “Why do you tell so many ghost stories?” I will be honest. I have never claimed to be a seeker of ghosts. You will not find me hunkered down in a haunted house with an ion counter in one hand, an infrared thermal scanner in the other, and a video camera clenched between my chattering teeth. I am afraid that I am far too lazy for such flagrant adventure. I am nothing more than a storyteller. I weave both history and folklore into the fabric of my yarning in an attempt to entertain whoever has gathered close to the campfire. I am not a historian but I attempt to keep as close to the truth of the matter as humanly possible.

So why ghost stories, then?

I usually answer the question by telling people how I used to listen to my grandfather’s stories when I was a boy. I liked his railroad stories, his hunting stories, and his fishing stories, but I loved his ghost stories best. As soon as I heard the rattle of a skeleton, the clatter-clatter of a rusty graveyard chain, or the creaking of a vampire’s coffin my ears perked up and opened wide. Ask any kid you know—ghosts are cool.

There is a great tradition of ghost stories here in Nova Scotia. You will find these stories carved in rock, rooted in timber, poured into the water, and wafting through the air that we breathe. The tales are many and varied, ranging from legends of buried pirate treasure, stories of eerie haunted houses and poltergeist pranks, and yarns of mermaids, selkies, and the spirits of the unavenged dead seeking out justice long after the grave has claimed their bones. I tell ghost stories to honour and keep alive this ancient gentle tradition.

One other question that I am asked frequently is, “When are you going to write another collection of Nova Scotian ghost stories?” Well, my first collection, Haunted Harbours, has done very well. So it certainly is time for a follow-up to that volume—and you are holding it right here in your clammy little hands.

For this collection I tried to touch on some of the older and more well-known tales, such as the mystery of Oak Island, the tale of the Mary Ellen Spook House in Caledonia Mills, and the haunting of poor Esther Cox of Amherst. Yet I have also spared no effort to unearth some of the lesser-known ghostly yarns of Nova Scotia, such as the tale of the Lunenburg werewolf and the Port Hood story “The Mark of the Fish.” Each of the two dozen tales contained in this volume is based on folklore and history that people have been passing around this province for the last two hundred years. The word “story” is just another term for the art of sharing experience. So let my words help you to share the experiences of people from long ago as they attempt to come to grips with the mysteries of the unknown.

From the moment you strike up a conversation with another human being you invariably find yourself talking in stories: “This is how it all got started.” “A funny thing happened today.” “You won’t believe what my mother told me.” And so, let me tell you one last story.

I spend a lot of time every year working in Maritime schools through the Writers in the Schools program. I talk to hundreds of kids. I teach them about the shape of the story, how to choose a voice, and how to use that voice well. And then, at nearly every one of my workshops, I like to end with a ghost story. I finish each ghost story with those two wonderful words: “The end.”

And then, after I have said those two words the kids will almost always respond with two more: “Tell another.”

Approximately forty kilometres southwest of downtown Halifax lies the little town of Peggy’s Cove. The village was founded in the year 1811 when the province of Nova Scotia issued a grant to six families to settle and build up the area. Very little has changed in this tiny fishing village since then—it now has a population of less than one hundred souls, all told.

Over the years, Peggy’s Cove has become famous as a kind of living Holy Grail for Nova Scotia tourism. Every year thousands of curious visitors flock from across the globe to walk upon the cove’s lonely rocks and search for the Lady in Blue—the ghost of a woman in a blue dress who is said to haunt these shores—and every year the local authorities warn the public of the dangers of clambering over those slippery, wind-blasted boulders. And yet every year—even in the wildest of weather—foolhardy visitors insist upon braving the wave-splashed rocks, risking at best an unexpected dunking and at worst death by drowning.

No one is really sure just how Peggy’s Cove originally got its name. Some claim that the name is n

othing more than the diminutive of the name Margaret, since Peggy’s Cove is situated at the mouth of St. Margaret’s Bay. Others will tell you that the tiny village was originally known as Pegg’s Cove—as it appears upon maps dating as far back as the late eighteenth century. Storytellers and folklorists will also tell of how, in the early nineteenth century, the town got its name after a sturdy little schooner was shattered upon the glacial granite of Halibut Rock, just a short distance from the current site of the much-photographed Peggy’s Cove Lighthouse. Coincidentally, this is also the story of how the Lady in Blue came to haunt the shorelines of this now-infamous tourist attraction.

Peggy’s Story

It was a stormy October night. The wintry wind howled like a mad banshee. The rain sliced down in sheer, horizontal sheets. The local folk called such a storm a Southeaster and on nights like this they laid extra firewood by their hearths, latched their windows, and barred their barn doors securely. Dories were hauled ashore and larger vessels were made fast with the tying on of extra hawser line. However, there was no such protection available for a brave schooner caught in the grip of the open sea.

The schooner’s captain leaned heavily against the wheel, pitting his faltering strength against the irresistible power of the current. It was no use.

“We’re going to lose her,” the first mate told the captain.

“Wrong tense,” the captain said. “The fact is we have already lost her.”

The first mate shook his head sadly. “Perhaps the men were right, after all,” he said. “We should never have allowed a woman on board. It is Jonah luck for certain sure.”

“Wrong again,” the captain corrected. “The way I count, it looks like we’ve got two women, not just one.”

It was true. The men had threatened mutiny when their captain had first announced that he was allowing a woman to sail with them. To make matters worse, the woman had brought along her young daughter.

In time the men had grown used to these unwanted intrusions. The ill omens promised by their gender were overcome by the woman’s kindness and comforting beauty. The men looked forward to watching her walk upon the deck in her favourite dress—a comfortable cotton dyed a particular shade of deep cornflower blue. The sailors even grew used to the sight of her young daughter, the cook would bake her sugar cookies, and the oldest of the men would always find the time each day to play her a tune on his wheezing old concertina.

Yet at a time like this, when the water was roaring and the waves were raging and the wind blew hard enough to blow the pucker from out of a whistle, old feelings would slowly surface.

“Two women on board is twice the bad luck by my mathematics,” the first mate pointed out.

“There’s no mathematics necessary in a situation like this,” the captain said. “Calculate it however you want to and it is nothing more than a matter of time before we all go down and drown.”

“So what do we do?” the first mate asked.

“What else can we do?” the captain replied. “Hang on until we can’t hang on any longer.”

The captain tried his best to bank his foundering vessel and turn her against the relentless current, but it was no use. His grim prophecy of losing the ship proved sadly true as the waves inexorably drove the brave schooner into Halibut Rock. The oak planks of the hull smashed up against the implacable granite with a jolting impact that drove the sailors to their knees. The waves splashed and swallowed the deck. Some of the crew tried to save themselves by clambering atop the schooner’s masts.

Meanwhile, one brave sailor saw fit to rescue the ship’s female passenger. Whether her presence had brought the vessel to its sorry state or whether it had been simply a mixture of bad timing and bad weather did not matter to this simple sailor. This was a woman in need and he was going to do his level best to see her to safety. “Get up on my shoulders,” he told her. “I’ll wade to shore.”

It was a foolish hope but better than nothing. The woman grabbed her daughter and clung to the brave sailor, who struck out into the current. He kicked away from the sinking schooner and tried his hardest to swim when he realized it was too deep to wade to shore. But the cruel Atlantic current pulled him under, and with his last gasp of strength he pushed the woman a little closer to the shoreline. In turn, she pushed her daughter towards the waiting rocks.

The next morning, when the people of the village came down to survey the aftermath of the shipwreck, they were amazed to find the only survivor—a fifteen-year-old girl who had washed up upon the shoreline.

The trauma of the girl’s ordeal had left her suffering with total amnesia. She could not even remember her given name. A local family by the name of Weaver adopted the child and gave her the name Margaret—or Peggy, for short.

The Lady in Blue

It is said that years later, as Peggy walked the shoreline, she saw what looked to be a woman in a blue dress—the shade of which was a blend of summer cornflowers, deep sky, and lonely regret. The woman did not seem to walk across the boulders, but rather glided, like a schooner in full sail. Peggy felt a cold breeze shiver across her bones and a salty tear splash at the corners of her vision. As she drew closer, she was amazed to see how strangely familiar the woman looked to her. It was almost as if she were staring into a mirror that had fallen into a quiet tide pool.

“I am sorry,” the woman said in a voice as soft as a summer breeze blowing in from the harbour. “I am sorry for leaving you.”

Since then the Lady in Blue has been reportedly witnessed by many tourists and residents alike in Peggy’s Cove. Some people will tell you that the Lady in Blue is actually the ghost of a woman who married a local man and then grew tired of the life of a wife of a fisherman. She supposedly abandoned her husband and children and sailed away on a Scotland-bound steamer only to sink just a few kilometres from her destination. Since then her spirit is thought to have wandered the rocky shores trying to make amends for her grievous treatment of her family.

Others will agree that the Lady in Blue was a fisherman’s wife, but they will add the wrinkle that she wanders the shoreline grieving for her husband, who drowned at sea while trying to support her and her four children on a fisherman’s wages. After the incident, she apparently gave her children up for adoption and then in a fit of sorrow starved herself to death, wandering the shoreline and wasting slowly away.

For myself, I believe that the Lady in Blue is the ghost of Peggy’s mother—the woman who gave her life so that her child might have a chance of survival. How very much like a mother to never forgive herself for drowning before her daughter was fully grown.

Whatever the story, there are an awful lot of people who have seen this sad blue spirit wandering the lonesome grey rocks of Peggy’s Cove. Keep an eye peeled the next time you visit the tiny village named after our heroine—and don’t get too close to those grey rocks or those cold, hungry waves.

About twenty kilometres southeast of the town of Yarmouth, in amongst the random scatter of islands that cluster about the larger and better-known Tusket Island—including Green Island, Bald Island, Sheep Island, and Goat Island—lies a bit of rock and timber that is known to the locals as Murder Island. According to Yarmouth historian R. B. Blauveldt, at the time of Yarmouth’s first settlement back in 1761, the skeletal remains of an estimated one thousand bodies were discovered bleaching upon the rocky shore of Murder Island.

Some people will tell you that these skeletons were actually the remains of the original diggers of the Oak Island Money Pit, which which we will get to later on in this collection. These people believe that the dreaded Captain Kidd transported all the witnesses of the burial of his treasure to this tiny little island off of Yarmouth, where he murdered them in a fit of cold-blooded savagery.

Several sources also suggest another origin of the name “Murder Island.” These sources talk of a great battle that was fought by a pair of warring First Nations tribes u

pon the island. They report that, according to an eighteenth-century French missionary who spent his life travelling from village to village, the Mi’kmaq and another tribe waged a great battle over a hidden treasure on the island. The resulting massacre was supposedly so brutal that the Mi’kmaq decided the island was bad luck and promptly paddled away from it, leaving it to the bones.

Do not be misled by any books that list this as a possible source for the original name, however, because when I looked into this version of the story, I learned that the sources in question were confusing Murder Island with an island in the St. Lawrence River known as the Île au Massacre (Massacre Island). There, according to local folklore, the Mohawk massacred a band of two hundred Mi’kmaq after trapping them in a small cavern.

So what really happened on Murder Island?

A Derelict Ship

On the fine Tuesday morning of October 7, 1735, the sturdy two-masted brigantine Baltimore set sail from Dublin, Ireland, bound for its home port of Annapolis, Maryland, with approximately five dozen souls on board—including eighteen crewmen and two ship’s officers.

The Baltimore was sighted once as it rounded Cape Sable Island over a month later. Then, early in December, the ship drifted into Chebogue Harbour, about six kilometres north of Yarmouth. When it arrived, the Baltimore was empty of crew and passengers save for a solitary survivor, who called herself Susannah. The deck was stained with blood and hacked in spots as if a great battle had been fought upon it. The ship had quite obviously been ransacked and there were no signs of cargo or valuables.

Susannah identified herself as the wife of the ship’s owner, Andrew Buckler. “We were off course,” she told the local authorities. “And we dropped anchor at Murder Island to refill our water and to forage for game.”

No one thought to ask just why the ship’s captain had bothered landing at Murder Island when the larger and more populated Greater Tusket Island was so close at hand. Perhaps they believed that the captain had been confused in his weariness. Perhaps it was just that no one could imagine the possibility that Susannah wasn’t exactly telling the whole truth of the matter.

Flash Virus: Episode One

Flash Virus: Episode One Cat Tales Issue #3

Cat Tales Issue #3 Cat Tales Issue #1

Cat Tales Issue #1 A Fine Sacrifice

A Fine Sacrifice The Lunenburg Werewolf

The Lunenburg Werewolf October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1)

October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1) Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3)

Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3) Haunted Harbours

Haunted Harbours Wicked Woods

Wicked Woods Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2)

Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2) A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9)

A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9) Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7)

Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7) Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4)

Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4) Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out

Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Sinking Deeper

Sinking Deeper Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5)

Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5) Big Hairy Deal

Big Hairy Deal Maritime Murder

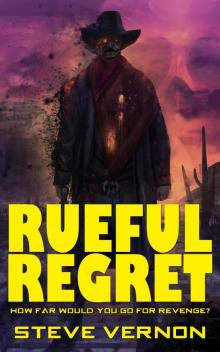

Maritime Murder Rueful Regret

Rueful Regret