- Home

- Steve Vernon

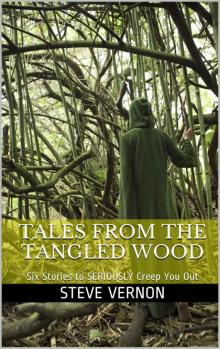

Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out

Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Read online

TALES

FROM

THE

TANGLED

WOOD

(Six Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out)

By

Steve Vernon

STARK RAVEN PRESS

What People Are Saying About Steve Vernon

"If Harlan Ellison, Richard Matheson and Robert Bloch had a three-way sex romp in a hot tub, and then a team of scientists came in and filtered out the water and mixed the leftover DNA into a test tube, the resulting genetic experiment would most likely grow up into Steve Vernon." – Bookgasm

"Steve Vernon is something of an anomaly in the world of horror literature. He's one of the freshest new voices in the genre although his career has spanned twenty years. Writing with a rare swagger and confidence, Steve Vernon can lead his readers through an entire gamut of emotions from outright fear and repulsion to pity and laughter." - Cemetery Dance

"Armed with a bizarre sense of humor, a huge amount of originality, a flair for taking risks and a strong grasp of characterization - Steve's got the chops for sure." - Dark Discoveries

“Steve Vernon is a hard writer to pin down. And that’s a good thing.” – Dark Scribe Magazine

"This genre needs new blood and Steve Vernon is quite a transfusion." –Edward Lee, author of FLESH GOTHIC and CITY INFERNAL

“Steve Vernon is one of the finest new talents of horror and dark fiction" - Owl Goingback, author of CROTA

"Steve Vernon was born to write. He's the real deal and we're lucky to have him." - Richard Chizmar

The Hunter’s Heart

The storytellers have it all wrong. Hearts are rarely sweet, nor are they tender. The heart is, without a doubt, the toughest meat in the carcass. You need to soak the heart in strong red wine to cook it properly, five days marinating is good, with the savor of a little garlic and some onion and a bay leaf and a stick or two of cinnamon. A lot of coarsely ground black pepper for certain sure, and a whole lot of tears.

The heart has a skin of its very own. It has a membrane that is both thin and strong that holds the organ safe against the thunderstorm of its own beating, or perhaps it merely hides whatever darkness that might be concealed deep inside.

“The girl must die,” was what you said.

You told it to me, my Queen. You threw my duty at me like a heavy and certain hunting spear. You commanded me, and because I had looked too long into the wishing pool of your eyes my heart softened. I would do whatever you asked of me.

I had no choice.

“Take her out into the woods, as deep as you can,” you told me. “And cut her heart out and bring it back to me.”

So I walked to the edge of the woods and I threw a stone into the darkness and I followed the path of the stone. You must understand that I never actually found the stone I threw, but I followed it nonetheless.

I wore a pair of iron soled boots and I walked into the deep north woods until my boot soles were worn down to the thinnest of tin. For a time I walked upon the meat of my own shadow and when shadow meat was worn to wind I learned to walk upon myself, until nothing was left but the trust of simple truth.

The truth was, I could not take her life, no matter how many forest shadows grew about me to hide the terrible deed that you wanted me to do.

“And when you return bring me her heart within a chest of black oak,” you said to me. “And I will burn it on a fire, so that I may know that she is truly dead.”

And it was here and only here that my heart failed me and my aim fell far short of my mark. Every time that I reached for the hilt of my hunting knife to end this bitter song, the hilt softened in my hand like wet willow and slipped from my grasp.

I could not do it.

I walked deep into the heart of the dark north woods, leading the girl behind me on a leash of softly chewed leather. She was a fair wee thing, her flesh as pale as the white snow of early winter, her cheeks as red as a pyre of burning roses, her hair as black as the ebony of moonlit grave shadow and for this they called her Snow White.

“Why come we so far into the dark north wood, hunter?” Snow White asked me. “Why do we travel so very far from the safety of my castle home?”

She looked at me when she asked the question, fixing me on the spot with her unblinking eyes.

“We hunt the deer, my princess fair,” I glibly lied. “You accompany me by the command of your good mother, the Queen.”

Snow White’s gaze iced over. Slow millennial heartbeats glaciated past before she finally spoke.

“My mother is dead,” the child coldly told me. “My birthing broke her soft heart in two.”

“That is a sad story,” I said.

At the heart, most stories are,” she replied.

“You have a point,” I said.

“What good is a hunter without a sharp spear point?” she asked, and then she shrugged, as if letting go of some great weight. Her voice gently deepened. For a moment I heard her mother speaking behind the mask of her hard words. “My father sleeps with another woman who leads him around by the leash of his man-meat like a well-trained hound. She calls herself the Queen, but in fact she is nothing more than the Royal Harlot and the castle bed-warmer.”

Old beyond her years and wise beyond time, that was all that the child would say.

*

“The heart is carved from a peculiar stone,” my father once told me. “There isn’t a hunter who can follow or find or fathom a whit of track upon its cold, hard and beating surface. Love is born there and harder things, but look not for any sign or readable track for the heart will show you nothing at all.”

My father’s words were carved from laws and judgement beyond question. He was a ranger, a hunter, who lived long in silence. When he spoke he hung each syllable upon a long steel rack, stretching the words for all to hear. His speech was ten hands tall and overshadowed anything I might possibly have to say.

“And a woman’s heart is hardest of all,” my father said, no doubt thinking of my mother who had left me alone one day while my father was out hunting far into the deep north woods. “There is neither a hoof nor a heel so heavy as to leave any kind of track across the soft elusiveness of that hard dark beating meat.”

My mother had never returned that day, and when my father came home with the meat of something small and tender and soft thrown across the hind end of his horse, he found me alone in my cradle, rocked by naught but the lonely west wind and my hunger belly squirming.

“Your mother is gone,” he told me there in my cradle. “And will no longer be here to wipe the snot off of your tears. You had best learn yourself to walk and talk, because tomorrow has rushed up upon you and left you with no one to fall back upon but yourself.”

So I stood up in my cradle and my first spoken words were lost in the clamour of my father hacking with his hand axe at the strange carcass he had brought home. He cleaned the meat and sliced it remarkably thin, bringing it to a long slow simmer in his largest cooking pot, weeping tears and sprinkling black pepper.

“Is this deer?” I asked him. “It tastes strangely.”

“It is dear,” my father replied. “Chew it slowly.”

My father was both ranger and a hunter, as was his father before him. He was one of those strange cold men who seemed to have a knack with murder. He would journey into the woods and the animals would lie down before him and beg for their death.

“The ancients talk of a drum,” my father once told me. “Crafted from a bit of wood carved from the heart of the tree that holds the world in its branches, and a bit of hide lifted

from the back of the immortal stag that grazes close by the tree.”

“What does such a drum do?” I asked, not more than a hand and a finger of years away from the cradle, and already out on my first hunt.

“It is said that if you beat such a drum on the hunt that nothing can escape your spear,” my father said.

“Surely, we must find ourselves this drum,” I said. “For the hunting would certainly be much easier.”

My father snorted his contempt like a stag snorting downwind of a clumsy hunter. I knew that snort far too well. I had heard it far too often growing up. My father laid his scorn upon me like a doting mother might lay an extra winter blanket.

“The only drum that a hunter truly needs beats deep inside the meat-cage of his chest,” my father said. “Always follow your heart, boy. It will you lead you straight trail-true.”

And then he slammed the hammer of his hand hard against his chest as if he hated what lay within, and I wondered what shadows might lay hiding deep inside my father’s heart.

*

Snow White and I tracked further into the dark north woods. I kept expecting her to ask me if we were there yet, as children will do on long journeys, but she said not a word. It seemed that she was a strong child, and her strength only made it all the harder for me to do what the Queen had commanded me to do. It was easy to kill a whining weakling. It was far harder to end the life of someone who deserved to live.

So I sought comfort through the distraction of explanation. I hid behind the mask of father and teacher.

“When you hunt the deer,” I told her. “You must always remember that a deer will travel in big circles. The deer will swing back around behind the hunter, hoping to evade the hunter’s spear by travelling in the wake of the hunter’s shadow.”

“So he comes back to us?” Snow White asked, wearing her eyes all gazing and fry-pan-wide.

She was growing as she walked, nearly as fast as I had grown when I’d first stood up from my cradle. Some children are never given the blessing of a slow-grown childhood. I believe they are the stronger for it, but not necessarily the happiest.

Snow White’s spirit stretched itself along the journey, reaching out into the form of a full grown woman who could raise and sharpen any man’s hunting spear with nothing more than a smile and a sly wink. Truly, she was the fairest of them all.

“Everything comes back to you,” I told her. “The ancients swear that the world turns in on itself every night, caught on a meat hook that is barbed between the sun and the moon.”

When my father told me this story he spoke of a deer that was tethered to the outside of the world. As the deer would circle the tether would turn the world inside out, over and over again. I know now that this story was nothing more than a simple and entertaining way to help me remember that a deer will often circle back on itself and that nothing in life lasts forever but time.

I readied my hunting bow.

“Here is a good place to wait,” I said. “Now hush.”

“Tell me a story,” she said. “Tell me a hunting story.”

And because it was Snow White, the fairest of them all, who asked me, my heart softened once again and I had to speak.

*

“Waiting is the hard part,” my father said. “A hunter needs to grow his patience in a long slow field.”

The two of us knelt there in the shadows beyond the cave of the great bear listening to the night talking to the wind and the trees. Ordinarily such brutes rarely bothered with the likes of men, and most hunters feared to take on such a beast; but this year the old bear had discovered the town’s cattle herd and was working a red-clawed path through the winter slaughter. The townsfolk had come to my father with a bag full of silver coins.

“If you have such silver,” My father pointed out. “Why don’t you buy yourselves some food?”

“We would rather use the silver to buy the bear’s blood,” The townsfolk said. “It walks a longer trail than the jingle of our coins.”

And so we dickered over death and bartered silver for blood and in the end the decision was inevitable. I knew it, my father knew it, and even the miserable townsfolk knew it. In a way, I think the great bear even knew what had to be done. And so we took our pay and travelled out into the woods and tracked the great bear to his cave.

It wasn’t that hard of a track to savvy, trailing after a long rope of cattle entrails and blood torn from the deepest of wounds. You could smell the carnage in the wind. The bear ate on the run, taking its nourishment and thus lightening its load as it travelled. It left behind a long vivid swathe of a path that was easier to read than a wide country road.

In time we came to the cave. My father lit a tinder bundle and placed it in a heap of dry grass with some green leaves for smoke. Then he blew his breath upon the kindle of the fire and I listened to the flames lapping through the grass until the fire rose up and the smoke rolled out before it.

“The larger the fire, the larger the smoke,” my father told me. “The smoke is the child of the flames.”

When my father spoke his every word was wrapped tightly in story-meat. You had to learn to chew upon the pronouncement of his sentences. Wisdom fattened and grew with every single bite. In short, his words had worth.

My father knelt by the fire, clothing himself in a hiding of smoke.

“Be careful,” he told me. “Be ready.”

The bear came charging out of the cave, in an avalanche of fur and talon and teeth and a wild hungry-bellied roar. The bear’s muzzle was tattooed with the memory of raw beef, red dirt streaks down its smelly bear belly, hunger and desire and rage spoored and spattered in large unmistakeable hieroglyphics.

My father rose up, his spear braced and ready. He flung it straight and hard like a one man siege engine. The point and shaft pierced the bear’s cattle-heavy belly. It was a solid hit, but not a good one. For a beast this size you needed to strike closer to the heart.

The bear kept charging, the butt of the spear waggling like an enormous phallus.

My father drew out his hand axe and his hunting knife.

“Ready yourself, my boy,” my father calmly said. “Your time has come.”

I stood up on my feet. It was time. Ever since my mother had left me in my crib-cradle, waiting for my father to hunt with, I knew this moment would someday arrive. I wished for a few more years in which to grow the knowledge and the cold courage to throw the spear in a proper manner, but my father and the bear gave me none of this. All that was left was the moment, and I had to act without thought, without words.

My father had time for one good axe swing, gutting a large blood track through the beast’s thick and woolly chest, peeling the bear’s fur away and revealing the meat that hid beneath the pelt. Then the bear was upon him and the two of them went down into the unforgiving dirt.

I ran up, holding my spear over my head with both hands praying and shrieking to the gods of the hunt. I struck hard from behind, a coward’s blow, a hunter’s blow. The spear slammed into the bear’s spine, I felt the meat parting before my spear head like water parting before the oar.

I was screaming as I slammed the spear home, yet my screaming was drowned out by the voice of another. My father shouted, a harsh barked out song of betrayal and disappointment.

I twisted the spear, trying to finish the bear off.

My father screamed again.

It was only then that I realized how deeply my spear had penetrated. It had passed straight through the bear’s heart and straight through the bear’s wound and straight into my father. The two spear-pierced hearts broke together, wringing out their blood in the dirt and pine bones and rock like a squeeze of freshly wrung sea sponge.

I knelt there as my father bled to death beneath the bear. He lasted far longer than the bear and taught me much in his tight-lipped passing. When it was over I painted my face with his blood and the bear’s blood. I hacked the bear’s head off and I placed it on the point of my father’s spear an

d I left it mounted over my father’s grave. I buried the bag of silver coins with him there as well. As I did so I could hear the scorn of my father’s derision, his words carrying soft on the twilight breeze.

“Dig the silver up, boy,” his memory told me as the tears of mourning slid down my evening cheekbones. “Your sobs and your snivels will not buy you meat when you’re standing alone, hard and hungry.”

I walked on for many long years, never looking back until now.

*

That is how the story happened, but this is how I tell it to the girl. I soften it and round it, cutting through the bitter hard parts and telling it all sweet and pretty.

My father would have spit upon the dirt to show his scorn.

“We were out on the hunt, waiting before the great bear’s cave,” I told her. “The villagers were hungry. They needed the bear’s meat. The bear charged me and I drove my spear into the beast’s heart but before the bear died it bore down upon my father and tore his heart out, eating it raw.”

Bluntly, I liked.

“And then what happened?” the girl asked me. “What did you do after your father was killed?”

“I buried my father, wrapped in the bear skin, and then I burned the bear’s cave down to the ground.”

“How do you burn a cave?” the girl-child asked me. “Aren’t they made out of stone?”

I felt ashamed.

She had caught me in a clumsy lie.

“Do not ask so many questions,” I told her.

It was more than pride that spoke behind my words. A story should never be appraised too closely. A story is a shadow sung and spun from beneath the reality of what really happened, and like any shadow it is often dark in the telling, and there are gaps, and there are moments that are left out of the song and deeds that we forget to tell.

It is the wounds of memory that we remember the longest.

“Hush,” I said. “The deer is upon us.”

And so it was.

A yearling, barely past the cradle-cap cosy of fawnhood. Hardly a killing worthy of any real hunter’s spear, but I had left the only real hunter’s spear that I knew of, back ten years ago beneath a dead bear’s skull, above an equally dead father’s grave.

Flash Virus: Episode One

Flash Virus: Episode One Cat Tales Issue #3

Cat Tales Issue #3 Cat Tales Issue #1

Cat Tales Issue #1 A Fine Sacrifice

A Fine Sacrifice The Lunenburg Werewolf

The Lunenburg Werewolf October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1)

October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1) Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3)

Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3) Haunted Harbours

Haunted Harbours Wicked Woods

Wicked Woods Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2)

Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2) A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9)

A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9) Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7)

Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7) Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4)

Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4) Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out

Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Sinking Deeper

Sinking Deeper Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5)

Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5) Big Hairy Deal

Big Hairy Deal Maritime Murder

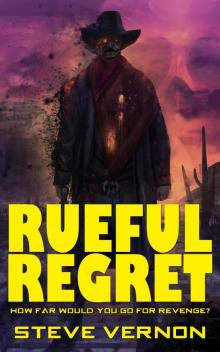

Maritime Murder Rueful Regret

Rueful Regret