- Home

- Steve Vernon

Haunted Harbours Page 3

Haunted Harbours Read online

Page 3

How long had this settlement stood here? Had it been abandoned by the French during their flight from the province? Perhaps the original inhabitants had been wiped out by a plague or a massacre. Nicholas didn’t know.

He warily explored the deserted settlement, not finding a single sign of the original inhabitants. Who were they? That they had been craftsmen was evident: the buildings were well constructed. Several gardens were carefully laid out and showed signs of recent tending. The houses were unlocked and fully stocked with all manner of furniture, clothing, silverware and many household necessities.

Where had the owners gone? If they’d fled the British advance, why hadn’t they taken their belongings with them? If they’d died of disease or been killed, where were their remains? If they had been massacred, why hadn’t their killers taken any of their belongings?

It was a mystery, but a blessing for Nicholas that he simply could not ignore. Here was an estate for the taking. He was a landowner.

He hurried back to Lunenburg, not telling a soul of his sudden great luck. The blockhouse was apparently forgotten to all, and Nicholas intended for it to remain so. He travelled to Halifax by boat and asked the British authorities for a grant of the land located seven miles up the LaHave River.

The authorities didn’t ask any questions. It seemed they had no knowledge of the previous settlement, either. They were more than eager to settle the untamed Nova Scotian interior wilderness. And why not? The sooner it was securely settled, the sooner the government could begin imposing taxes. They happily gave Nicholas a grant for one thousand acres of untouched land in and about the little horseshoe-shaped harbour that is now known as Horseshoe Cove.

Nicholas hastened back to Lunenburg and quickly moved his family from their temporary town dwelling up the LaHave River to take possession of the abandoned blockhouse.

Within a year Nicholas began displaying the effects of his sudden good fortune. He discarded his sensible homespun jacket, his wool stockings and trousers, even his battered felt hat and wooden sabots. He began dressing in the fancy garments he’d found in the abandoned houses of the settlement. He took to riding and spent much of his time wandering and admiring his lands and his buildings.

Instead of working the land for a living, Nicholas amassed a small fortune by selling off firewood cut by his sons. Nicholas, a landowner now, considered himself far too dignified for such menial labor. One wonders what his sons might have thought about this.

Nicholas saved his peasant attire for the times when he would have to travel to Lunenburg. He only wore his fancy duds within the security of his own landholdings. Perhaps he feared the thought of other people learning of his good fortune, or perhaps he was afraid that they might see through his pretense and laugh at him. In any case, as soon as he returned to the sanctuary of his own lands, off would come the peasant garb, and he would immediately change back into his fancy wear, sometimes as he crossed the border of his own land. Many a hunter has told the tale of seeing old Nicholas tugging on his silk trousers in the heart of the darkened Nova Scotia forest.

Every Sunday Nicholas would ring the blockhouse bell, thanking God for his good fortune. You could hear it, clear to Lunenburg, tolling long and low.

All went well for many a year. Nicholas lived out his charade, relying on the wealth his family’s efforts provided. He occasionally carried some of the valuables from the settlement to be sold off at Halifax. He never sold any of the clothing. He couldn’t part with any of his lucky finery.

Then one night Nicholas was awoken by the sounds of a great drum beating in the heart of his richest woodlot. “Someone is stealing my timber,” he shouted to his family. He dressed himself in a combination of his finest garments and peasant wear, whatever was closest at hand. With a loaded pistol in his hand, and armed with the indomitable sense of his own self-righteousness, he strode boldly into the forest depths, following the sound of the beating drum.

Within a half an hour Nicholas found himself in the heart of a vast Mi’kmaq gathering. Believing that his right of ownership granted by the Halifax authorities would somehow impress the Mi’kmaq, Nicholas brandished his loaded pistol and ordered the group to leave his lands.

Nicholas was inches away from his own death. Even though the tribes had long ago made peace with the British, it was still considered most unsociable to wave loaded weaponry in a stranger’s face. Only the fact that the Mi’kmaq thought him more funny than dangerous saved his life. They took his pistol and turned him out into the darkness.

Nicholas brooded through long days and nights, hearing the Mi’kmaq ceremonial drum beating in his very own woodlot. Three days later when the Mi’kmaq left their ceremonial grounds, Nicholas moved in with all of his sons and cut that section bare. He even deigned to pick up an axe himself. He worked from sun-up to sundown, tearing his favourite pilfered silk shirt in his effort to make that section of land absolutely inhospitable. Nicholas hauled the felled timber to Lunenburg and had it loaded on a ship, and he personally saw to the delivery in Halifax. It was his best load yet. He returned home to Lunenburg with his pockets jingling and he grinned with the sweet taste of revenge.

His grin faded when he returned to his estate and found that his entire family had been murdered. Even his dog had been gut-ted. The furniture had been broken up and his fine clothing torn and burnt. He knelt over the ashes and howled like a gut-shot wolf. They say that the townsfolk heard his screams all the way back into Lunenburg; if they didn’t hear the scream they certainly heard the bell tolling long both day and night.

Eventually Nicholas wandered back into the settlement of Lunenburg, a shadow of his former self. His fine clothing was torn into rags upon his back. His eyes were dulled with madness.

The settlers rallied to his cause and gathered a hunting party of stout German and Dutch farmers and sailors armed with muskets and pistols. They managed to hunt up several Mi’kmaq, hanging four of them in front of the site of the massacre at Horseshoe Cove. Doubtless many of these Mi’kmaq were innocent, and a lot of blood was needlessly spilled, but the townsfolk felt that justice had prevailed. They shipped two of the Mi’kmaq survivors to Halifax for trial. One died in prison and one escaped.

For a time Nicholas Spohr lived alone in the town of Lunenburg, getting drunk every night with what was left of the profits of his last wood sale. He swore that he would never return to the accursed blockhouse at Horseshoe Cove.

Then one moonlit night he disappeared, walking into the Nova Scotian woods. Most of the townsfolk figured he’d been drunk and had simply wandered off, but a few wiser folk knew better. They searched for three days and finally found him outside of the blockhouse, prostrate upon his wife’s grave, dead from hunger, exposure, and the ravages of grief.

They buried him there, outside of the blockhouse that had promised him so much happiness. For many a year the site was shunned by whites and Mi’kmaq alike. Yet in the restless nights of autumn, when the wind is dancing with the clouds and talking of the snow that soon will fly, the story goes that you can hear the sound of an iron bell tolling a low and mournful dirge, even though the blockhouse has long since vanished. Local folks who hear it, even today, will simply shrug their shoulders and walk on: Old Nicholas is ringing his bell and walking a lonely vigil through a woodlot that has never grown back quite right.

5

THE

GHOST-HUNTER’S

WHISTLING GHOST

LIVERPOOL

In her 1968 collection Bluenose Magic, Helen Creighton tells of a lot of different ways that you can slay a witch or rid yourself of a ghost. Silver will do it; water will too. So will fire and salt. I’ve since heard the following old story of a rogue witch-hunter who used just such a technique to make a small living, although I have reason to believe that his motives were less than silvery pure.

Back in the early 1800s in the Liverpool area, there lived an old man named Hank O’Hallorhan. Hank was a bandy-legged fellow, not half as old as he looked, but as laz

y as a fat frog wallowing in the bottom of a mossy well. Hank used to be a sailor, but no ship would have him for very long because of his bad habit of whistling too much. Hank was a nervous little man who found relief through whistling, something no sailor could stand due to the old superstition that an idle whistler could just as easily whistle up a storm as a tune. So Hank became a hunter, though of an unusual sort. He’d go from town to town and enter someone’s house, making sniffing sounds and saying, “I smell a ghost,” or “I smell a witch.”

If he claimed to smell a ghost he’d fire a charge of black powder up the chimney flue to frighten the evil spirits away. If it was a witch he was chasing, he’d beg a dime that he’d cut up into slices to fire up the chimney, because everyone knew that silver was the only thing that could slay a witch. He’d beg a dime at every house, but would only slice up the one; even a witch hunter needs to make some kind of living.

One day he showed up at an old woman’s house and swore he could smell a witch. Actually what he’d smelled was a brace of freshly baked apple pies cooling by the windowsill. Hank figured on making a bit of money and perhaps a piece of pie or two. He walked up to the front porch, whistling like a flock of lovesick canaries.

The old woman, whose name was Annie Tuckins, fixed Hank with a hard, sharp stare.

“Damn a man who whistles,” she said. “He’s either got something on his mind, or absolutely nothing at all.”

“Oh grandmother,” Hank said, figuring he’d get farther by talking politely. “I smell a witch in your chimney. She’ll cast a spell on your baking for certain sure. Would you have a dime that I might use to banish her?”

The old woman looked up from her baking, half-amused by O’Hallorhan’s gall and half-bothered by his unasked-for interruption.

“Only a dime? Witches come cheap in these parts,” she said. “And how much would it cost me to banish you?”

“You may laugh,” O’Hallorhan replied. “But I tell you this true. There are witches in every corner of this sainted province. They’re easier to find than toads in a peat bog. Standing in the shadow of every black cat is a witch in waiting. They might be your neighbour or they might live a half a dozen counties away. There’s no telling where a witch’ll turn up, if she puts her mind to it.”

“So how can you tell if one is a witch or not?” the old woman asked, playing along with O’Hallorhan’s banter.

“Oh, there’s many a way you can tell if a person is a witch. For instance, if you lay your broom across your front doorway, the witch cannot cross it.”

The old woman snorted. “It sounds to me like a perfectly good way to trip yourself going into your house.”

O’Hallorhan laughed easily. An acre of brooms could not trip up such a sly-talking, fast-thinking man as he.

“And a young woman such as yourself would jig lightly over a palisade of brooms, now would she not? Heel and toe, you’re a light stepper, like the fog running in from the bay.”

“Flatterer. So here’s a piece of silver and that’ll buy your trick, won’t it?”

O’Hallorhan palmed the old woman’s coin and pulled out one of his own, a tin disc he’d bartered from a tinker. He cut the tin disc up with his case knife and carefully loaded the fragment into his musket, after filling the gun with powder.

He tamped the makeshift metal shot down securely with his ramrod.

“You ought to oil that rod before it rusts,” the old woman pointed out.

“It rams as straight as the day it was first hammered out,” Hank said with a wink.

He cocked back the hammer, inserted the firing cap, and let fly, firing the homemade ball of tin straight into the old woman’s fireplace. The cheap powder he’d used smoked the kitchen out.

“There you go, good grandmother. It’s done and done. The witch will bother you no more.”

The old woman laughed. “She never bothered me in the first place. So off with you then, you have my silver and my blessing. I’ll count it an experience and thank God for it tonight in my prayers. It’s reckoned fine good luck to help a beggar.”

O’Hallorhan bristled at the word “beggar,” but he said nothing about it. He had eyes for the old woman’s apple pie. “It’s better luck to feed one, Granny. Why don’t you carve me off a slice of that hot apple pie, and a wee nugget of cheese if you have it?”

The old woman’s humour hardened. “Be off with you. You’ve palmed my dime and fired that wee bit of metal you thought to pass for silver and you’ve fouled up my kitchen with your dirty cheap powder.” She grabbed her broom up from the floor. “Leave this house now, or I’ll put this broom to a better use than tripping up witches.”

O’Hallorhan wouldn’t have it. “I’ll have that pie before I go. I can still smell the witch, and she needs another blast or two.”

“You’ll have the end of this broom, and you’ll be picking splinters for a fortnight,” the old woman said.

O’Hallorhan looked her in the eye. “Well I’m walking that way,” he said, pointing towards Liverpool. “And there’s a lot of houses between here and midnight. It’d be a shame if word got around of how I smelled a witch in your house and you wouldn’t let me smoke it out.” He had her then. She knew the trouble that O’Hallorhan could start for her.

“Take the pie and be done with it,” she told him.

But O’Hallorhan would have nothing to do with that. In his eyes he had to earn the pie fair and square. So he loaded up his gun, but in his hurry and cheapness he slid in a plain lead shot, once again keeping the dime for the silver.

He fired a blast up the chimney but it ricocheted off the chimney stone, and struck O’Hallorhan square in the heart, killing him stone dead. The old woman was sorry to see O’Hallorhan dead, but not sorry enough to forget about retrieving his pilfered silver.

For years afterwards, the old woman would hear a whistle up the chimney flue, and even though most folks swore it was nothing more than a hole left by O’Hallorhan’s shot, the old woman swore it was the ghost of the old witch-hunter.

“Shut up, you old whistling crook,” she would yell, “or I’ll fire a whole barrel full of silver up that flue and finish you good and proper.”

6

THE

JORDAN FALLS

FORERUNNER

JORDAN FALLS

Storytelling isn’t like writing. You’ve got to put a little more of yourself into it when you’re sitting there staring at your audience across the flicker of a campfire or into the glare of stage lights. So I hope you’ll forgive me if I talk a little of my own life now.

I was raised in the woods of Northern Ontario, high in the shield country, about twenty miles north of Sudbury in a little town called Capreol. My mom and dad had married a little too early and went their separate ways, and my brother Dan and I were raised by our grandparents. Dan is still out there in Capreol, working for the CNR. My mom went back home to Yarmouth, Nova Scotia, and Dad eventually moved out west to Blairmore, Alberta. Being a working man, Dad had little time to travel, and neither did I.

I can count the number of days my father and I had any chance to speak with each other. He once travelled to Nova Scotia for two weeks to come see me. We talked as best we could, shared a beer or two, and tried to make up for the years that had been left behind.

He was a lonely man, I think, but happy nonetheless. He’d found a good woman who put up with his lonely ways. He became the president of the Blairmore Legion and was responsible for the building of a brand new legion hall.

He died at age fifty-eight of a sudden heart attack. I received the telephone call late at night. “Your dad’s had a heart attack,” Lila said. I remember thinking how my grandfather had lived through three such heart attacks. “He’ll have to slow down,” I said. Only it was a little late for that. The old reaper had already slowed Dad down for good.

I flew out to Blairmore to see him one last time. I touched his cheek in the coffin, cold and ruddy from a life spent working outdoors.

; The night before my dad died I dreamed of him. In my dream we were sitting in the living room I’d grown up in and we were watching an old western on the television. We talked and got along, as if time had not passed. And then he turned to me and said, “I’ll be going now.”

I do not talk of this much, but that is how it happened. A night later I stood in my kitchen receiving the hardest telephone call I’ve ever had to take. Was it a coincidence? Maybe, but I tend to believe that my father’s spirit came to me in my dream to make peace and to tell me to hang onto my memories of him in any way I could.

In the winter of 1888, a great blizzard ravaged the eastern coast of the United States and the Maritimes, dumping over four feet of snow and paralyzing transportation, yet there were far more chilling events about to transpire.

In the tiny village of Jordan Falls, just outside of Shelburne, Ephraim Doane awoke in his bedroom, screaming as if the devil were at his very door.

“Abandon ship!” he called out, sitting upright in his bed, terrifying his young wife Mabel.

She rose and made them a cup of tea, allowing Ephraim to catch his breath.

“What’s wrong?” she asked.

“I’ve had a terrible dream.”

Now Mabel was descended from a long line of highland women, and she knew enough about the power of dreams. Spirits talked to you in dreams, and gods and devils walked hand in hand through the mist-ridden foothills of sleep.

“Tell me about it,” she said to him.

“We were out at sea in the midst of a terrible gale. The ship was heel-toeing like a step dancer’s boot. I looked out into the roiled-up waters and saw your eyes looking at me, and then somewhere high above my head I heard the mainmast snap and fall.”

Flash Virus: Episode One

Flash Virus: Episode One Cat Tales Issue #3

Cat Tales Issue #3 Cat Tales Issue #1

Cat Tales Issue #1 A Fine Sacrifice

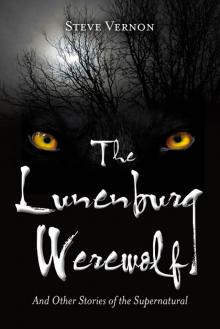

A Fine Sacrifice The Lunenburg Werewolf

The Lunenburg Werewolf October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1)

October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1) Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3)

Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3) Haunted Harbours

Haunted Harbours Wicked Woods

Wicked Woods Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2)

Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2) A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9)

A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9) Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7)

Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7) Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4)

Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4) Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out

Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Sinking Deeper

Sinking Deeper Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5)

Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5) Big Hairy Deal

Big Hairy Deal Maritime Murder

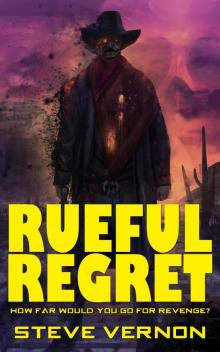

Maritime Murder Rueful Regret

Rueful Regret