- Home

- Steve Vernon

Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4) Page 3

Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4) Read online

Page 3

I longed to revenge my country's misfortunes. We had roused a sleeping giant and were forced into retreat and surrender as wave after wave of American carriers, warplanes and men rolled over our diminishing forces. As the great B-29 Flying Fortresses rained firebombs upon the sacred walls of the Emperor's palace. They were burning Japan. They were burning it with bombs that fell like fiery rain upon the homeland.

"Devil!" Shouted the bomber pilot. "Devil!"

I looked forward. There, ahead of us, was an American fighter. A Mustang, named after a horse. The Mustang was strangely alone. The Americans had the gift of numbers. They flew in packs and hordes, finding courage in multitude.

Where were his comrades? I looked to the heavens and saw nothing. He was alone. Would he shoot us down? Even one Mustang was a dangerous opponent for an overloaded Hamaki bomber.

"Slow down. Let me fly," I urged, knowing that the weight of my Ohka suicide plane would hinder the bomber's maneuverability.

But the bomber would not let me waste myself. He flew boldly forward, straight at the American fighter. Would he crash him? Ram him full on?

A part of my spirit mourned such a waste, to trade plane for plane against such an army was not a plan at all. Yet part of me longed for the great taking, for the chance to knock down one of the enemy, even at the cost of my own plane and life.

The Hamaki pilot opened fire with the 7.7mm machine guns in the bomber's nose and soared over the fighter plane, raking him from front to back.

Why doesn't the American turn, I wondered. Why doesn't he try to circle us and come from behind? He's faster and far more maneuverable. Why doesn't he outfight us?

The Hamaki pilot bore down upon the fighter, lifting slightly to fly over him, raking him with machine guns. I was close enough to see the American pilot, hammering in vain at his instrument panel. Something was wrong. There was some kind of malfunction hindering his fight.

A streamer of flame bled from the side of the tiny armored fighter. We passed over him, our tail cannon making short work of his aircraft, chopping him to pieces in the sky, hard hammering fist bursts.

"Banzai!" shouted the pilot. Ten thousand years. The empire will last ten thousand years.

"Banzai," I dutifully echoed. It was a magnificently lucky kill. Even I, in my inexperience knew this. Had there been another fighter or had the downed fighter not suffered from mechanical malfunction the outcome would have been greatly different. The Hamaki bomber and my self would have been sent spiraling to the ocean below.

We had lost before we had even begun. It was only a matter of time. Japan was beaten. It was as inevitable as rain. Even the generals knew this. Yet surrender was not an option. It was better to die doing something than to let go of what you held.

That is what the netsuke was for. Travelers carried them as good luck charms, as worry stones, as pieces to fiddle with; but their real purpose was to remind you that life was to be lived as long as you could hold onto something.

I touched the release button. Why had I yelled at the pilot? How foolish I had been; forgetting in my panic that the key to my release lay in my hands.

I stroked the netsuke.

I could see the smoke clouds of the American fleet steaming above the water. The distant fighter planes like hordes of insects swarmed high overhead. Soon we would be close enough. Soon I could release myself and crash into an American vessel.

The Hamaki waggled its wings to show the pilot’s good spirits. I knew that it had taken nearly all of his pitiful supply of ammo to bring down the fighter. I knew that many more fighters waited before us. I knew that the sea would be thick with destroyers and cruisers and battleships. I knew that the sky would erupt like a thousand volcanoes with the American antiaircraft gunnery.

I knew so much.

“An empty skull is a useful soup bowl,” My flight instructor told me. “Pour it full with knowledge and drink it up.”

I knew that I would be out there alone, perhaps. There were few enough Kamikaze planes left in Okinawa. Those few that got through the American screen would be as useless as a single grain of rice cast into the belly of a famine. It didn't matter. I needed to find my chance. A voice from the ocean called to me like the north spirit calls to the compass needle.

The enemy was lined up below me in the Okinawa waters at the doorstep of my home land. The Japanese army was dug in as deep as moles and would exact a heavy toll on the big nosed American invaders but in the end it was inevitable. At best they might give the American forces a severe case of indigestion but the white men would still feast upon Japan's bones.

It was a season for dying. The politicians talked of duty and sacrifice and how they would strew the entrails of the Japanese people across the beaches of our homeland. They prophesized victory snatched from the gaping jaws of defeat.

Fools.

I didn't care. I had seen enough of my homeland, gutted by the great bellied American bombers. Tinderbox cities climbing heavenward on wings of smoke and flame. Lives made light as windbound cinder. The stink of charred meat, scorched bones. Men dancing in the arms of fire, screams drowned in flame.

A wheel turned and the shadow fell against us. We watched as a huge unstoppable tortoise clambered up a beach, the Americans reclaiming each of their fallen territories, inching closer like a great inevitable beast.

How we suffered. I watched children gnaw upon rats and worse.

I wanted to strike back. I wanted to do something.

To do anything.

In the end that is all the gods give us is the opportunity to choose our own life and our own demise and the illusion of accomplishment. There was nothing left but to die and die well. To make my death glorious.

So now as the end of our war and the end of our nation loomed as inevitably as the setting of the sun, I waited for my chance to crash headlong into a carrier or a battleship. I wanted to crash into something large, something that would make a difference, if only to me.

A carrier would be best. The Americans built their carriers thin and large. Big fat hollow eggshell targets that dreamed of explosions and drowning. A single well placed crash plane could easily sink an American carrier and thus sink all of the planes the carrier bears.

The battleships were too armored and well gunned. It is a heaven sent miracle when a plane got close enough to impact upon the deck of one and more often the plane burst into flame, seared the hide of the big gunned beast-ship and accomplished nothing. Even the 1200 pound high explosive payload of my Ohka was but a single fart in the eye of a hurricane.

I saw them now, the battleships, the cruisers, the destroyers. The landing ships and the fat transports. Our planes were among them like mosquitoes. The anti-aircraft bursts covered the sky like an army of clouds. How easily the Americans swatted our planes.

I watched below me as a cascade of Shinyo attack boats scudded out across the water, aiming themselves towards the American battle fleet. The Shinyo were long fast explosive laden speedboats with no more chance of getting close enough to do any significant damage than a bumblebee attacking a whale. The escort ships whittled them down with blasts of automatic gunfire. Only one got through the defenses and slammed into a transport. The transport heeled to one side and began to sink.

Banzai. Thirty eight boats have crippled one transport. We had shot our final bolt. There would be no reinforcements. This was our last naval battle. Even now the last few mighty ships of our navy were steaming out of Japan, steering for Okinawa with the intention of joining in combat with the American fleet. It was a fool's gesture. The American carriers would not let our few ships penetrate. Our fleet would be sunk long before they were within sight of Okinawa.

Japan was dying. The Shinto priests talked of the great typhoon that washed away the Mongol navy of Kublai Khan, defeating his attempt to conquer Japan. Later on, in the Sino-Japanese war another typhoon foiled a thrust from the Russian navy. I have heard the stories.

I did not know if these Kamikaze typhoons were the product of some

heavenly miracle or a simple coincidence, the danger of setting sail in monsoon weather. The priests and politicians had talked and believed in it long enough that the simple act of meteorological upheaval had become the stuff of legends.

I fingered my netsuke. It was my totem. I focussed my thoughts, my energy and my mind through its essence. I was the serpent. I moved through the water, my shadow passed over it, hiding in the waves and the light.

You could see my head, you could see my tail but never both at once. I was a mystery, moving in shadow. I was a river, come from many streams. I was the ocean and you could not count every drop of seawater.

My spirit was large. If only there were an equally large force on Japan's side. We had no allies left. The Americans had the English, the Australians, the Chinese and even the Russians. The Germans had fallen. The Italians had never learned to stand. Now the world came together to make war over Japanese waters. It was only a matter of time before the country fell.

A flying splash of metal color blasted before my eyes. I saw a Mustang fighter, machine guns hammering like a shout of carpenters, nailing my Ohka, bullets ripping through me.

I was dying.

Not yet. I could not die yet. I squeezed the netsuke. It slithered in my hand, slick with my freshly spilled blood. I poked at myself. I felt soft and burning, loose pieces dangling, my entrails twisted in my fist as I tried to hold myself together in a cage of badly punctured meat.

And then it happened. The waters below me steamed and churned like a pot over-boiling. Something rose up out of the waters below me. Was it a submarine? I prayed it was one of ours. A mighty I-class submarine that would send a bellyful of Long Lance torpedoes into the guts of the American fleet.

And then I saw it below me. I saw a serpent, huge and long. I must be dreaming, maddened by pain and death and futility. I blinked away the tears that swam before my eyes. This was no time for sentimental outbursts.

My eyes stung and burned like salt water.

No, it was more than that. I saw salt water. I saw through the eyes of something that moved through the water.

And then it happened. The serpent rose up, its scales running like a thunder of rainbows, gasoline over water, gunpowder flames and the running of burning meat. From out of the water the serpent rose hard and heavy, my netsuke-beast, my soul running through its spirit in long tangled dream of vengeance. A serpent, huge and long and sleek with arcs of grain cut and gouged from its hide.

"Do you see that?" I called to the Hamaki bomber pilot.

There was no answer. The Hamaki pilot was either struck dumb or blinded by the oncoming danger or perhaps simply a victim of mechanical failure. The pilot did not answer my cry. He did not give any sign of seeing the great beast in the waters below. He was a blind man flying high above me, not seeing a thing.

I looked down at the beast in the water. It was my netsuke - larger than a mountain, larger than an island. I fingered the netsuke in my hand. It felt warm to the touch, like a fire being kindled. It felt warm and wet with my blood, a seedlet being born. We sailed and soared together, my netsuke-beast and my great bomber, the air and water combined.

This is the miracle, I thought. This is the gift that will bring us victory.

The priests were right.

My grandfather was right.

My father was right.

We soared into the heart of the American fleet. The netsuke beast threw itself across the deck of a puny destroyer and snapped the lesser ship in two like a chunk of rotted driftwood.

I tasted blood and meat. I heard screams and the tearing sailor cloth. I snorted at the reek of fat white American flesh. High above me the Hamaki bomber twisted and danced through the horde of oncoming fighters. A nearby Zero blazed a trail of cover for our advance.

My netsuke beast rammed full into a landing craft. Even this high up, I heard the screams of the drowning soldiers. I tasted blood and terror and felt the bones of fighting men grind in my netsuke beast's teeth.

The netsuke beast flexed its mighty wooden fish hide thews, forcing a great cloud of heat through the water. The drowning soldiers cooked like fish. The air stank of burnt meat.

The heat was hatred for the invader.

Yes, but mostly hatred for defeat.

"Banzai," I shouted. Ten thousand years. The empire would live ten thousand years.

And then something turned. An American cruiser placed herself next to my netsuke beast and raked its back with shellfire, punching and tearing great holes in the wooden beast's back.

"Banzai," I shouted, willing the netsuke beast straight into the soft metal of the great cruiser. I felt the sea beast’s determination, felt the deck of the American cruiser bend beneath my sudden weight.

A battleship roared out a wall of fire and steel, its16 inch guns spouting retribution, raining down upon my netsuke and the cruiser, all dead alike, torn by a hail of flying metal.

"Release, release!" shouted my bomber friend as the fighters tore past his defense and raked him with a hail of heated bullets.

I hit the release button and felt the yoke slip way and my Ohka sailed under the spirit and power of its own wings. The Hamaki roared past me taking out two enemy fighters. The flames burst like fireworks. I prayed that the explosion would take out more fighters but my prayers were wasted. Twenty more American fighters swooped past the exploding Hamaki. I powered my aircraft down towards the battleship. There were no carriers in sight. I looked to my left and right.

The cruiser erupted, a magazine hit by a stray shell, heaving the bulk of my netsuke beast into the air. I felt the wind as my bulk heaved up from the waves.

I felt myself widen in the blast. I was everything and everywhere all at once. I was born from many waters. I was the sea, the land and the air.

As I roared into a steep descent I saw my great netsuke beast, wallowing beneath the combined barrage of a half a dozen capital ships. I heard its voice, soft as melting honey, glowing inside my brain.

I am dying, the netsuke beast said. I am dying of the future. Time has left. Time slipped away.

I saw the battleship, fat and tempting below me.

I saw the netsuke beast being torn into a skeleton of kindle-wood and prayer.

There were tears splashed in the great beast's eyes. Red salty tears. Tears from the drowning men, the burning pilots, the marines splashed overboard like green clad rocks.

I knew now why the sea tasted of salt. There were tears from every side, raining down. In war all sides must sing of sacrifice. I turned my rudder and pushed my plane screaming down into the grateful beast's heart. We would die together, I thought. Our death would be a pyre for the American fleet to ground itself upon.

As I hit I felt a great wave rising up and a mighty monsoon rose from the impact of my plane against the netsuke beast; a monsoon powerful enough to halt the American's advance.

The monsoon slowed them.

Somewhere far beyond my dying vision, an American admiral paused as a single cup of coffee grew cold. He waited the storm out and then turning to light a cigarette with a single match, he ordered the invasion to proceed.

In six weeks time Okinawa was a memory. The Americans paid dearly.

Our country held its sacred past, a memory melting in its outstretched hands, held the dream a moment longer.

And somewhere off Saipan a B-29 warmed up. A pilot and his crew sipped cups of bitter coffee and dreamed of Hiroshima, and the bomb belly glowed and chuckled like a fat woodstove.

The waves rolled onwards, kissing the waiting shore with countless salty tears.

The Takashi Miike Seal of Approval

You can call me Simon but don’t let this collar fool you. I’m not one of the good guys. A good guy wouldn’t be caught dead standing outside of a man’s office at this time of night.

It was raining but I didn’t mind the weather. If you ignored the rain for long enough it usually went away. Everyone but Noah said that. The man I was waiting for stepped outside. His name

was Lucius Cartland Maugham. He was a portly man with a stately side to side swagger like a sashaying zeppelin. He wore a sport coat that had been carefully tailored to hide the milk fat that was cloying on his well fed bones. Beneath the sport coat he wore a pair of equally tailored acid washed jeans. Acid washed jeans. I never did understand that concept. Paying extra up front to make sure your new pants looked old. It was amazing what people would pay money for.

I stood in the shadow of a dead oak tree, dressed in a tattered black slicker and a pair of black denim jeans. He didn’t see me at all. That was the beauty of homelessness. People learned to ignore you or curse you, just like the rain.

I stepped out and grabbed my chest, falling towards him. The problem was, I couldn’t remember which arm was supposed to hurt while experiencing a heart attack.

Left? Right? Fuck it.

I grabbed his arm as he reached out to catch me. I let myself sag a little, feeling him take my weight. He didn’t catch me like he was concerned. He caught me sort of gingerly, like he was afraid I would dirty his hands. I swung up fast, getting a lot of hip into it, driving two hard hooks deep into the soft of his belly. He lashed out once, tagging me on the right eye. Not bad for a fat man.

I sank a third hook. It was his turn to bend over. I felt his belly heave up like a jellyfish that hadn’t been stomped quite hard enough. I prayed he didn’t puke on me. There was a lot of fastidiousness going around tonight.

When I was sure he wasn’t going to regurgitate his last box of Krispy Kremes I caught his head by the ears and brought my knee straight up. I nailed him right on the chin, banging his teeth together with a satisfying click.

Then I dragged him back into his office.

The night’s work had just begun.

*

Lucius Cartland Maugham’s face turned the tight purple blue of a frozen violet until I loosened the double width duct tape gag that covered his nose and mouth. The video camera hummed contentedly.

“If you try to scream,” I said. “I will replace the duct tape and you will asphyxiate. You may have heard that asphyxiation is a painless way to die. Don’t believe everything you hear.”

Flash Virus: Episode One

Flash Virus: Episode One Cat Tales Issue #3

Cat Tales Issue #3 Cat Tales Issue #1

Cat Tales Issue #1 A Fine Sacrifice

A Fine Sacrifice The Lunenburg Werewolf

The Lunenburg Werewolf October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1)

October Tales: Seven Creepy Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 1) Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3)

Roadside Ghosts: A Collection of Horror and Dark Fantasy (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 3) Haunted Harbours

Haunted Harbours Wicked Woods

Wicked Woods Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2)

Two Fisted Nasty: A Novella and Three Short Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 2) A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9)

A Hat Full of Stories: Three Weird West Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 9) Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7)

Bad Valentines: three twisted love stories (Stories To SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 7) Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4)

Do-Overs and Detours - Eighteen Eerie Tales (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 4) Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out

Tales From The Tangled Wood: Six Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Sinking Deeper

Sinking Deeper Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5)

Bad Valentines 2: Six Twisted Love Stories (Stories to SERIOUSLY Creep You Out Book 5) Big Hairy Deal

Big Hairy Deal Maritime Murder

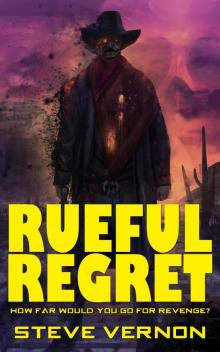

Maritime Murder Rueful Regret

Rueful Regret